WRITINGS

When the Ganga becomes the Padma: Settling in Bangladesh

June, 2017

Unpublished text, Dhaka, 2017.

Flow

All things take a radical turn as the Ganga becomes the Padma. But it is not precise where the Ganga flowing over a vast part of the subcontinent, commandeering its historical and geographical imagination, all of a sudden finds itself no longer a riverine force but part of the largest delta in the world.

The Padma is the last leg of the Ganges before it converts into a mush of foam and mud at the mouth of the sea. It is the final stage of Ganga’s operatic metamorphosis, from a mountain trickle to an epic river, and to a grand finale at the meeting of three rivers. The point from where the Padma begins, ambiguously from the stream of the Ganges, to the bowels of the ocean, is about 258 km of the total stretch of 2600 km of the Ganges. But from where the Padma begins and where it dissolves, both ambiguously, it describes an incredible phenomenon of geological and hydrological dynamic. By the time the Ganga is the mighty Padma, the water is an oceanic expanse – in the designation of Sir Charles Lyell who in the nineteenth century observed ocean currents: an “oceanic river” – by the whose banks are often so far apart that it is one is hardpressed to call it a river.

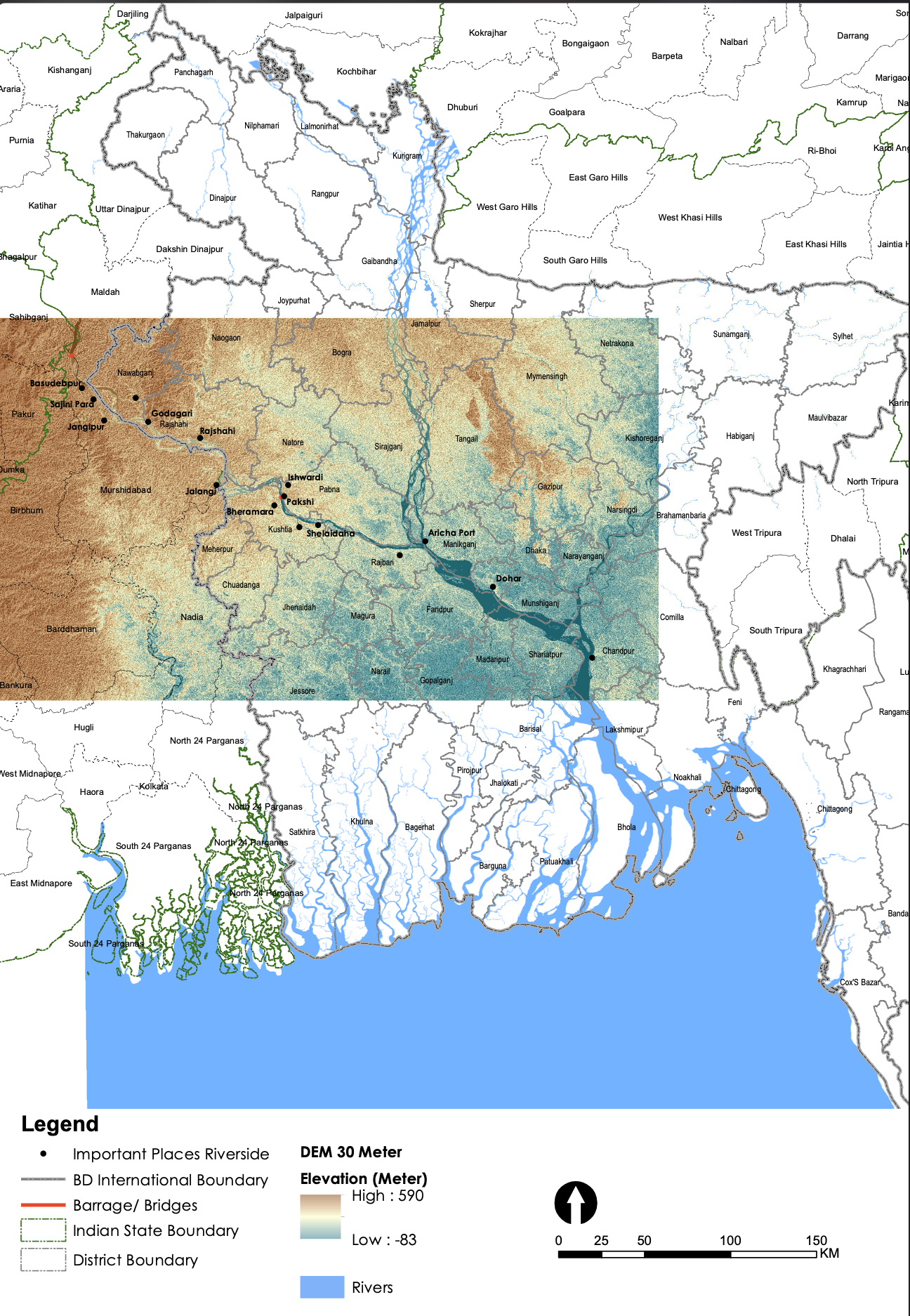

From the Ganga to Padma is not simply a name change but a qualitative shift, in which the Padma along with two major river systems inaugurates the delta. With 144,000 sq km area, it is also one of the most populated and densest, and with an ancient production of rice, perhaps the most fertile. With a population of 200 million (of which 160 million is in Bangladesh), the delta is a “nation of water upon land,” creating a highly precarious and contested environment that. writes the landscape architect Kelly Shannon, “is essentially a gigantic floodplain, with the Ganges (called the Padma) carrying the silt of India and the ashes of millions of Hindus, the Brahmaputra (called the Jamuna), principle river of the eastern Himalayas, joining in what is known as the Mighty Meghna, which then flows southeast to the Bay of Bengal.” It is also the instance where the Ganges meets its other riparian protagonists, the Brahmaputra-Jamuna coming straight down from the north. Soon after meeting the Meghna river further east that comes down from the north-east, the Padma ends in the Bay of Bengal, or known as Bangoposgar from the 2nd century CE.

Borne out of the hydrogeological chemistry of the three rivers, land formed primarily by silt deposits, that is constantly shaped and reshaped by these three rivers and their hundreds of tributaries, which themselves are perpetually shifting and changing. All this dynamic gives the land an amorphous nature, and characterizes the region’s climate, topography, ecology, and sociology.

The Ganga-Padma is a force of flow that carries with it materials that rematerialize as the alluvium of the delta [quantity?]. Stones and pebbles from the hills of the north, debris of humanity from the middle of India, and ashes of the deceased are all pulverized and agglomerated, and resurface as land and island formations – the chars – along the Padma.

Before trains and roads, it was the Ganga-Padma flow that linked Bengal with the north India. Giant boats with gigantic sails, with names like Mayurpankhi, Aswamukhi, and Singhamukhi, plied on these waters. Visitors or observers like Abul Faz’l, Tavernier, Hedges and Rennell, and many others, must have traveled down this mighty stream to the heart of the delta, and returned the same way.

In this paper, I take a downward flow in a river narrative, from where the Padma may have begun in the west of the Bengal delta to the point where it vanishes in the great aquatic convulsion in the south-east.

Bhati

From the plains of Indraprastha or the Lal Quila of Delhi, the uniqueness of the eastern region, known variously as Vanga or Bangala, was recognized with a certain degree of apprehension, mixed with wonder and derision. The Vedic Aryans considered the region “impure,” outside the pale of Aryavarta. Sanskrit texts mention that because of the impurity of the eastern land, anyone venturing out there will require ritual purification before returning. Even the Turks, Afghans, and Persians who gained control over northern India considered the eastern region with mixed perceptions, describing it as dozakh pur-i-niamat (hell full of boons). In reference to its geographic constitution, the Mughals called the land bhati, the downstream of the river.

The delta or bhati, is where hilsa fishes spawn, rivers become rivulets, rivers meet rivers, rivulets become wetlands, rivers meet the ocean, and land is held captive in a great rhythmic churning of mud, silt and sludge. Great nets are cast in the waters, and settlements small and large thrive and plunge in the treacherous waters. In a great alchemy that is part mystical and part tragic, land-forms arise again in some unexpected, unmapped waters, and thrive. In such an excruciatingly flat terrain, a few centimeters matter in defining what is wet and what is dry, which in turn describes two cultural paradigms: one organized by an aquatic lifestyle, and another by a dry ideology, so to speak.

A world of moistness and fecundity makes the bhati a predominantly water-based civilization, where cosmological and valorized concepts are generated from riverine practices and agricultural rituals. It is also a matrix of “rice culture,” where rice is not something merely consumed but is the basis of value-construction, of a collective ethos and mythos. In the Bengal delta, rice cultivation is an existential occupation; the production of rice is the production of a world-view. Two paradigmatic figures populate the Bengali imagination: the man with the plough (langal), the farmer; and, the man with the fishing net (jaal), the fisherman. The boatman and the boat are also an integral part of this narrative.

Who named the Ganga as Padma? In Bangla, padma is “poddo” meaning the lotus flower, another name for the goddess Lakshmi. Does the name change indicate some kind of shift that is perceptually cultural, but also fundamentally meteorological and material? The Padma certainly belongs to the Bengal Delta and has shaped the material and psychological imagination of its peoples. The Ramayana mentions the transformation of three gods into riverine forms: Ganges as the male Bhagirathi, Lakshmi as Padma, with Lakshmi representing feminine wisdom, and Saraswati as herself; it seems that from the start Ganges and Padma have always been two and different. The Ramayana also mentions a muni named Poddo, who instructed the Ganges to flow in the east, and the name may have come the muni, as was Bhagirathi from the muni Bhagiroth.

Modern texts describe the Padma from the point where the Ganges meets the downflow of the Brahmaputra-Jamuna up to Chandpur at the mouth of Meghna river. Popular perception however stretches the origin of the Padma further west from Chapai Nababganj district, which is almost coincidental to the political boundary of Bangladesh, or further west in West Bengal where the Hooghly begins its tributary flow away from the Ganges, to Chandpur, the port-hub at the cusp of the oceanic river.

Another way to think about the Padma is a distinctive dynamic that the Ganges generates or encounters as it enters the geography of flood-plains, in how courses have shifted and widths have fluctuated in which the landscape of the hinterland is consequently affected. The tumultuous Padma have shifted its course drastically in the last several hundred years. Once the Padma flowed much closer to Dhaka, but now lies about 46 km to the south of the city. Regions south of the Padma, all the way into the Sundarbans and the ocean, is a hydrological outcome of the Padma and it’s dynamic. The rivers and rivulets, emerging primarily from the Ganga-Padma flow, create that incredible weave of land and water that is the mark of the delta.

Barrage and Bridge

By the time, the river known as Ganga reaches Rajshahi, it is already the mighty Padma; it has entered the historical landscape of Bengal, and the political terrain of the nation-state of Bangladesh. Rajshahi is north of Ganga-Padma, a town of mango groves, picturesque riverbanks, and historical urban relationship with the river. It is the first big town that boldly faces the Padma highlighting the point that there is also urban life on the banks of the Padma. Organized riverside parks on chars that are adjacent to the city are a distinctive feature of the town. Very few towns have such incredible adjacency of an unsettling river and a settlement.

About 100 km upstream from Rajshahi is the Farakka Dam in western Bengal, completed in 1975, to tame and reorient the Ganges. Between Farakka and Rajshahi, an arbitrary weave of a political boundary takes hold, through which flows the uncertain, unruly flow of a riverway. Deceptive enterprises of certainties and containments spring up in the form of bridges, barrages, canals and embankments.

While the original purpose of the Farakka barrage was to divert water from the Ganges to the Hooghly in order to flush out sedimentation near Kolkata harbor, the natural flushing has not been as successful as planned; additionally, riverbank conditions on the Ganges have been adversely affected due to the high level of back waters. A more critical consequence envelops the bhati: the barrage affects the flow of the Padma that in turns impacts the ecology of fishes, mangroves, salinity, river tributaries, and human lives. A point of contention between Bangladesh and India has led to constant negotiations between the two neighboring countries that share a mighty river. In the meantime, Bangladesh considers building the Ganges Barrage project with the projection that it will hold back water in lean periods, generate electricity, and reroute the waters of the Brahmaputra towards the Hooghly.

Barrages, bridges, canals and embankments are modern engineering responses to the management of the environment, but as with such large-scale infrastructural projects that intervene with river flow and its waters, unforeseen ecological and human consequences may emerge. Anthony Acciavatti describes the various modern engineering enterprises surrounding the Ganges that has transformed the landscape of central India as, what he describes as, the “Ganges Water Machine.” Following the Farakka Barrage, the Padma Bridge may be the largest infrastructure construction planned across the Padma.

Initiated in 2010, with construction ensuing and expected to be completed by 2018, the Padma Bridge will be the most ambitious undertaking of the Bangladesh government. At 6.15 kilometers (3.8 miles) in length, being one of the longest river crossings in the world, the Padma Bridge will be a landmark structure. With a two level passageway, one for road vehicles and another for rail for a total length of 6150 m, and with cost of USD 3 billion, the Padma Bridge is also an engineering challenge. “One of the greatest challenges,” writes Robin Sham of AECOM who are designing the bridge, “to long-span bridge engineering are the forces of nature. Recent catastrophic events around the world reinforce the fact that nature can be destructive to infrastructure.” Taking on that challenge, as well as controversies around funding by international agencies that stalled the project before it could start, the Bangladesh government is constructing the project mostly from its own resources with a special resonance to building a bridge on one of the largest, unruly rivers in the world.

Exchange

If the Ganges is the river par excellence in the Indian imagination, the Padma circulates similarly in the Bengali imagination, in geographic, literary and mystical terms. Manik Bandhopadhay’s novel “Padma Nodir Majhi” (Boatman of the Padma, 1936), with life and travails of people along the riverbanks, becomes an allegory for humanity in the delta. Centered around the emergence of a mysterious island (char), a freshly brewed landscape, where a Muslim trader wants to establish a new community – a kind of a utopia – Padma Nodir Majhi depicts the tidal fluctuations in the precarious lives of Hindu and Muslim boatmen and fishermen, and an intertwining of their intimate lives. The Padma landscape is a constant reminder of dissolutions and emergences, both of the material landscape as well as human lives. In narrating the plebeian culture of the Padma, Padma Nodir Majhi represents the rhythm of the Padma, its oscillation from being a bountiful source to a treacherous actor, from inciting hope and submission simultaneously.

Sheliadah in Kushtia is a place 40 kms (25 miles) south of the Padma, and the estate of the Tagore family of Calcutta; it is there, and on the nearby banks, a great exchange took place between an urban cosmopolite and rural humanist. The poet Rabindranath Tagore stayed at Shelaidah intermittently for nearly a decade from 1890, from where the river Padma was few miles away. Rabindranath’s father, Dwarkanath Tagore, had boat-builders from Dhaka build a boat that the poet used to ply on the terrain; it was called the Padma.

The Kolkata elite that Rabindranath Tagore belonged to and the people of the Padma – as represented in Padma Nodir Majhi – are worlds apart (amplified by the fact that the Tagores were landlords in the Shelaidah area), but the river, and the banks and the various canals and channels, had a lasting impact on the great poet. Rabindranath by then was already renowned for his work, having composed many songs drawing from Western, Hindi, and Asian sources, and having already created his inimitable musical genre. During his stay at the Padma estate, Rabindranath befriended disciples and friends of the baul mystic Lalon Shah, such as Gagon Harkara and Kangal Harinath, who with their folk mysticism and rural ethos, had a transformative impact on the poet already in a mature stage of creations. Rabindranath wrote some of his key works including Sonar Tori and translated the Gitanjali into English while staying in Shelaidah. Drawn so much to Lalon’s ideals, Rabindranath Tagore often called himself “Rabindra Baul.”

In a poem, Rabindranath writes: “He had his poet’s welcome from the river Padma/ and the morning star through the intervals of bamboo leaves on her bank./ The dark masses of cloud had spread before him/ a purple shadow on the distant rain-dimmed forest;/ his eyes had followed the track of noisy girls to the river/ along the shady village lane/ and enjoyed the duet of colours under the sunset sky/ in the blossoming field of mustard and linseed sown together./ He gazed and said, ‘I love it.’

What Rabindranath Tagore was to Calcutta-centric western Bengal, Lalon Shah of Kushtia was to the east. A mystic, singer, composer, and folk philosopher, Lalon’s songs have often been described as the “lyrics of the Padma.” It was in the southern landscape of the Padma, living in the zamindari of the Tagores, amidst the life-world of the people akin to that depicted in Padma Nodir Majhi, in the whittled and braided matrix of land and water, that Lalon developed his humanistic spiritual position. Avowedly neither Muslim nor Hindu, but both, and more, Lalon epitomized a spirituality and humanity that also broached on social reform in that rural universe. Lalon was deeply embedded in the ethos of rural Bengal, the everyday of common life particular to that landscape, but that combined Sufi mysticism, baul poetry and Baishnav spirituality. Ever alert to the call of the self against the self-centered politics of identity that pitted one religion against another, Lalon was to wonder: “Shob loke koi Lalon ki jaat shongsharey” (people wonder what is Lalon’s identity in society). Rejecting classism, social hierarchies and any kind of fractious ideology, Lalon used his music in the capacity of social transformation and to affect individual psyche in understanding life anew.

Even if Lalon’s direct meeting with Rabindranath is uncertain, he is known to have visited the Tagore family in their Shelaidah zamindari. The only portrait of Lalon, from 1889, was sketched by Jyotirindranath Tagore in his houseboat on the Padma.

Since Lalon worked orally, and in the language and mood of the common people, much of his work is not recorded. Kangal Harinath Majumdar, a disciple and friend of Lalon and a pioneering rural journalist from Kushtia, collected many of the songs that were perhaps shared with Rabindranath. Even if a direct meeting between Rabindranath and Lalon did not happen, something substantial did take place through the exchange with the disciples; Rabindranath’s journeys in the Padma landscape also impacted his intellectual and spiritual position. What with his spiritual romanticism derived from the beauty of the aquatic landscape, Rabindranath became enamoured with the folk melodies that are part and parcel of that milieu. “During the monsoon,” Sadya Afreen Mallick writes, “Tagore was drawn to the jari, shari and bhatiali songs of the boatmen. Many of Tagore’s compositions came to reflect this period, depicting the life of the working class.” Supported by Kangal Harinath, Rabindranath collected a set of songs by Lalon, and published them in the Calcutta based monthly Probashi. Gagan Harkara’s songs, especially “Ami Kothaye Pabo Tare” were also published. Rabindranath’s song, “Amar Shonar Bangla,” the national anthem of Bangladesh, was composed and based on the baul tune of Harkara’s song.

There in the delta, along the shores of the Padma, where things are raw, elemental and primitive in the best sense, the intellect is thwarted if not subdued for either a romantic twist or spiritual turn for the Kolkata elite. This meeting of the elite and the elemental, with Lalon as the anchor for the latter, produced some of the finest works of Rabindranath. Even as late as the 1990s, Lalon’s net caught the imagination of the American poet Allen Ginsburg to write:

It’s true I got caught in/ the world/ When I was young Blake/ tipped me off/ Other teachers followed:/ Better prepare for Death/ Don’t get entangled with/ possessions/ That was when I was young,/ I was warned/ Now I’m a Senior Citizen/ and stuck with a million/ books/ a million thoughts a million/ dollars a million/ loves/ How'll I ever leave my body?/ Allen Ginsberg says, I’m/ really up shits creek [After Lalon (1992), partial]

Land/Water/Wet/Dry

From where the Ganga becomes the Padma settlement patterns change and the precise calibration between dry and wet becomes uncertain. Kelly Shannon notes that topographic differences of a few centimetres define what is wet and what is dry, or what will be mostly wet or dry for most part of the year, and for that matter what kind of habitat, occupation or human activities will take place. In such conditions, cities and settlements, those stubborn edifice of dry practices, remain fragile.

This is clay country where the land is at the mercy of the water. Before clay, a product of moisture, can solidify into a crusty, soily substance, it is awash with water again, shaped and reshaped in a seasonal rhythm. Land has no self-defining ontology; it can only by hyphenated with water for water is everywhere and everything. How to make habitats here? How to build settlements? How to rethink the city?

That Bangladesh is rich in alluvium and tragedy is a persistent narrative. Padma is the femme fatale in Tagore’s poems, the “rakkhasi preyasi,” the witching lover, one who cannot be fully trusted, but one who charms and delights, and draws us to its bosom like moth to fire. Borne of the bewildering dynamic of the delta, with its confounding flux and flow, and the seasonal gift of flood and the occasional scourge of cyclones and tidal waves, the people of Bangladesh demonstrates a resilience that others are mystified about. When Katrina hit New Orleans, that far away city at the edge of America, newspaper reporting the events suddenly found a kinship between people of the Mississippi with their tribulations and people of the Bengal delta with their resilience.

The people of the delta – the Bengalis – have an ambivalent relationship with cities. Poets and writers of the land sing the sweet songs of villages and versify the vileness of the city. Even when they live and enjoy the city, they dream of the little village through the poet of rural ethos Jasimuddin’s comforting image of salubrious vegetation and that untranslatable sense of being wrapped in “maya-mamata.” Apu, in Satyajit Ray’s filmic Pather Panchali (based on Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s novel) reclines wistfully in his hovel in a grimy neighborhood in Kolkata, playing the flute like a Krishna dislocated from his arboreal and aquatic habitat.

Dhaka city, once intimate with the Padma but now at a deceptive distance, is a poster child of a city that is at odds with its larger landscape. The transformation of Dhaka and its regions, along with its physical and social landscape, have been relentless and brutal. By creating one landfill after another, emaciating rivers and canals, and decimating flood-plains and agriculture, Dhaka makes for a perfect candidate for an urbanization without urbanism.

An urbanism for Dhaka needs to be conceptualized from the hydrological property of the delta. The theoretical challenge is this: Surrounded and infiltrated by a labyrinthine and delicate network of rivers and canals, tissues of wetlands and floodplains, and organic formations of mounds and settlements, Dhaka needs a new approach to city-thinking and city-form. The biggest challenge in the recomposition of Dhaka lies in engaging its landscape reality – the dynamic hydrology of the delta. With an ever expanding city, the dynamic also involves an ecology of the edge.

The edge of Dhaka city is a precious landscape where new patterns of space need to be organized in response to a hydrologically fluctuating condition that includes flood-plains, wetlands, and agricultural fields. Innovative ideas, with new visions for housing typologies, transport network, and civic spaces, will have to negotiate between the hard city and vast fluid landscape of the delta. What is particular with Dhaka is how landscape reorganization is happening at a rapid pace to create (dry) lands for industries and then residences for the upper class in a global chain of complicities and linkages.

Official planning is unable to conceptualize this edge, to recognize that the edge is its own ecology and a critical one. Without that realization it is easy to participate in the destruction of the city’s hydro-geographical landscape. Dhaka is not alone in this urban upheaval. Following Dhaka’s lopsided planning, other towns and settlements are also pursuing a dry paradigm.

A re-appreciation of the edge is critical to anyone deliberating on the city in the delta: The geography of the edge is determined by the built-city marching up to meet the “non-urban,” a magnificent but precious terrain of land-water mass made of wetlands, flood-plains, canals, and agricultural fields, the matrix of the delta. The edge is where the dry meets the wet, the “developed” meets the “primitive,” and infrastructure meets the structure-less. This is also where the urbanite meets the farmer, the land grabber discovers his opportunity, and the uprooted often makes her habitation. Site/s of the biggest battle in the city, the terrain of the edge is determined by the presence and flux of water. No planning scheme will work for Dhaka, or any other town, if this simple equation is not recognized.

Nothing short of imagining a new landscape of city-form will offer a salvation for cities in the delta such as Dhaka. The edge conditions of Dhaka presents the possibility of re-negotiating the social and economic, as well conceptual, separation between city and its conventional anti-thesis, whether the village, flood- or agricultural plains. The edge is where new forms of space organization in response to a fluxed landscape will have to be reorganized, along with newer types of economic and social opportunities. In the meeting of an older form of the city with agricultural land-form and hydrological landscape, a new conception of a city will have to be developed that integrates urbanism, agriculture, infrastructure and flooding. Only then a plan for Dhaka will be commensurate with the dynamic of the Padmatic landscape.

Flow

The hilsa, the national fish of Bangladesh, literally a bone of contention between the two Bengals, is a pure product of the Padma. At soccer games between East Bengal and Mohun Bagan clubs in Kolkata, fans of East Bengal is known to wield hilsas as a mascot, and a sign of its prowess. On the other side, fans of Mohun Bagan flash the golda chingri (shrimp) as their team ‘fish.’

This soccer chauvinism around fish is a reflection of a cultural fission between the two Bengals, with people from the bhati referred to as “bangals” in Kolkata parlance, and people on the western side of this arbitrary divide as “ghotis.” “Now for the uninitiated,” writes Shomini Sen in a newspaper article on the contest between hilsa and chingri, “Bangals are those whose roots belong to the other side of Padma river – now known as Bangladesh. While Ghotis are those whose roots are in western side of the same river. There has been an underlying rivalry between Ghotis and Bangals since time immemorial which has spilled on to the football field as well. While Bangals are known to support East Bengal Club, Ghotis are ardent supporters of Mohun Bagan.” Depending on which team wins, fans and supporters will organize food festivities around their fish mascot. Such is the passion around hilsa that when East Bengal wins against Mohun Bagan, the demand for hilsa will shoot up in markets in Kolkata with even the fish running out of stock early in the morning. The price of the fish will also shoot up.

Being the emblem of the Padma, the hilsa is also critical in the economic and ecological life of Bangladesh. Generating about 1% of Bangladesh’s total GDP, nearly a million people – fishermen and traders – are occupied with the hilsa. As an anadromous species, the hilsa breeds upstream in the fresh water of the Padma with the larvae hatching from free-floating eggs. A large sized female hilsa can produce up to 2 million eggs. After growing for a short period in the river water, the fish swims down to the mouth of the river-sea, south of the confluence of Padma-Meghna, feeding on planktons and algae to return to the river as mature fish to breed again. The cycle is completed in a flow and counterflow in the river-sea ecology.

However hilsa production is depleting reflecting a combined economic and ecological impact. Apparently, low water discharge from the Ganges due to Farakka Barrage and consequent increase in siltation is a principal factor. Catching of the juvenile fish when they are migrating towards the sea thus disrupting the cycle, loss in spawning and feeding zones in the Padma, and pollution of its waters, and disruption in migratory routes due to increased human and mechanized movement are some other causes for the adverse effect on hilsa production.

It appears that while waters, silt, ashes, and debris flow downstream, hilsas move both upstream and downstream. The hilsa tells the story story of an entire human and physical landscape that runs from the depth and flow of the Padma river, to the banks where fishermen and boatmen have led lives from immemorial times, to the traders and middlemen and their transport network on water and road that comprise of the modern economy, and to the markets and shops of big cities like Dhaka and Kolkata where the fish completes its economic cycle, and finally to the dinner plates where a national, cultural and culinary life is fulfilled. But recent facts indicate that phenomenon of the hilsa is neither stable nor guaranteed. Neither are the formation and flow of the Padma, and in turn an entire cultural and geological landscape.

The author thanks Afifa Razzaque, Arfar Razi, and Sanjoy Roy for research assistance.