WRITINGS

Wet Narratives: Architecture must recognize that the future is fluid

May, 2017

Published in The Architecture Review, May 2017.

It goes without saying that water is the stuff of life, and if the levels of world waters rise, the stuff that will make life difficult. We are made of water, we drink water, we wash with water, we purify water, we purify things with water. There is too much water, there is too little water. Before water is somewhere, as landscape architect Anuradha Mathur and architect/planner Dilip da Cunha argue, it is everywhere. Be like water, Bruce Lee implores. Despite the ubiquity of water, its measure is diverse and polyvalent.

Whether framed through political ecology or literary devices, water remains an existential theme. If catastrophes and perils determine design motivations in the 21st century, water is up there – whether as threat of sea-level rise, depletion of coastal cities and communities, tidal surges, hazardous contaminations, or for that matter, as life-threatening scarcity. Besides channeling the discourse of disaster, a narrative of water is already inducing alternative strategies in design thinking. A wet narrative asks for a new design intelligence that is perhaps better conveyed by the term ‘waterness’ than a tagged-on qualifier like the ‘aquatic’, ‘liquid’ or ‘hydraulic’. In overcoming the deep dichotomy of a wet and dry ideology, and a prejudice of the dry land codified, for example, as ‘land use’ in planning vocabulary, new motivations entail a phenomenological appreciation of ‘water as ground’, and an urban and landscape strategy: wet urbanism.

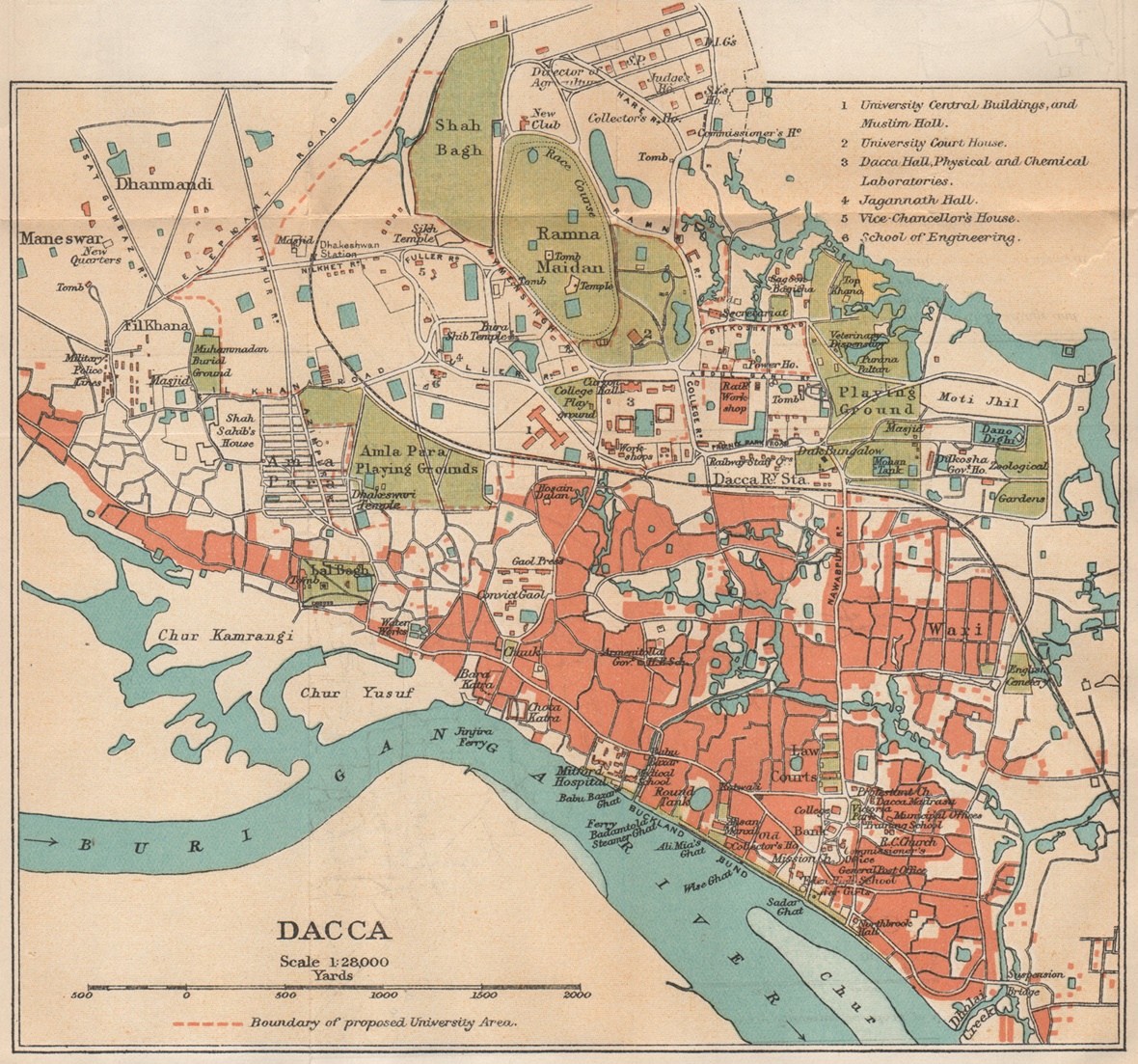

Once upon a place and time, the city of Dhaka – Bangladesh’s capital and now a poster-city for wild urbanization – emerged cautiously from an irascible landscape known as the Bengal Delta. A 10-minute ride outside the metropolitan madness still shows the aquatic reality of the land – rivers, canals, waterways, ponds, floodplains and agricultural fields completely girdle the city. But few people recognize that Dhaka is a tender land-mass, virtually an island framed by three rivers and a fluid landscape. From furious landfilling operations, motivated by real-estate economy, to infrastructural interventions, precipitated by a perception of peril, the precious landscape remains savaged. Dhaka is symptomatic of most cities in powerful hydrological milieus (deltaic, riparian or coastal) and undergoing furious transformations, where practices of planning, whether official, private or impromptu, have succumbed to the regime of a dry ideology.

A deltaic geography is an immense force of flow. Water cascading down from upland mountains brings pulverized remains to the floodplains below in the form of sand, silt and mud, depositing them in an unpredictable geometry of landforms and waterways. Flows and overflows – more commonly understood as ‘floods’ – impart to this landscape a corrugation of flat plains, ponds, muddy enclaves and ‘lowlands’, all of which constitute the distinctive but amorphous topography. As ‘delta urbanist’ Kelly Shannon observes, in such an excruciatingly flat terrain a few centimeters matter in differentiating what is wet from what is dry.

Both mystical and cosmogonic as a phenomenon, the chars – land formations caused by the dynamics of soil-shifts and water flows – rise annually in the delta waters to inaugurate an Adamic landscape. Delicate chars appear one year in the complex choreography of land and water to disappear the next, while more or less stabilized ones become sites of settlement. A char is thus a reminder of an earlier turn of a river and deposition of silt to form the new land-mass, demonstrating a geohydrological process in action. In this motile landscape, where a site is hardly reliable, and the architectural foundation is literally wobbling, the conventional parameters of city building and architecture are brought into question. Born out of a fluid dynamic, in which place-form is more critical than object-forms, chars pose a conceptual challenge to the imagination of landscape norms, and to the relationship between architecture and landscape.

From the heart of the present city, Dhaka and the delta appear as two separate entities, antithetical and strangers to each other. Fed on dry ideas, planners and policy-makers remain befuddled about envisioning or even managing a city in such a toiled terrain; any deliberation begins with an assumption that a water terrain is unreliable for the city and must be thwarted. In the horizon of the contemporary city, the delta does not even appear in the consciousness until a deluge comes, like clockwork, annually and unmistakably. The past tense of Dhaka being a deltaic city marks both a failure to innovate planning positions and exacerbation of the ‘natural’ opposition between city and landscape.

Conventional urban planning has basically become the production of land, the manufacture of dryness. Landfills, embankments, bridges and roadways have supported the technology of a dry culture, pitting the city against the aquatic delta. In the schism between dry and wet, dominant planning practices have not only obscured immersive worldviews, but also enforced a limiting measure on an otherwise prodigious and unruly landscape represented by the delta, whether it be the Gangetic, the Mekong or the Mississippi. How can one find an urban and architectural relevance in such a fluid dynamic?

(Partial Text)