WRITINGS

Sangath as a Landscape Event

May, 2017

Published in Balkrishna Doshi: Architecture for the People, edited by Mateo Kries, Jolanthe Kugler and Khushnu Hoof (Vitra Design Museum), 2019. An earlier version appeared in The Companions to the History of Architecture, Volume 4, edited by David Leatherbarrow and Alexander Eisenschmidt, 2017.

As twin projects, although separated by about ten years, Sangath (1979-81) and the Husain-Doshi Gufa (1992-94) heralded a new fantastic dimension in modern Indian architecture, and a turning point in the oeuvre of the master architect Balkrishna Doshi. Similar to the awe and intrigue generated when Ronchamp was first unveiled, the two projects presented a new plastic language and building ethos, reincarnating ancient and phantasmagoric sentiments in an India that was then positioning itself for a new global and corporate trajectory. Both projects are also powerful essays on architecture’s inscrutable relationship with the landscape, a theme that eluded most architects until then. Deliberately produced and articulated as an “event” in the landscape, in which architecture is intimately implicated, the projects mark a new synthesis of building, topography, planting, and landscaped elements.

Sangath sits between two phases in the oeuvre of Doshi: between cubic masses raised aloft in the landscape, and a crustacean creature lying embedded in the ground. The former belongs to a group of projects from the Institute of Indology in Ahmedabad (1957-62) to the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore (1977-85), and the latter is expressed singularly at the unusual Husain-Doshi Gufa (1992-95), a progeny that followed Sangath. Sangath is a key project that inaugurates the mythopoeic dimension in Doshi’s work that takes him from an explicitly rational and objective approach to architecture towards an openly oneiric and phantasmagoric realm.

As a stalwart among the first generation of Indian architects following the national independence in 1947, Doshi took on that enormous task of graduating India towards a “brave, new world” as imagined by the first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Since then, through a powerful body of work, Doshi was instrumental in framing a modern architectural idiom and ethos for India. This was made possible through his personal commitment to nation-building and a unique background of working with two foremost form-makers of the modern period. The experience of working with Le Corbusier in his Paris studio (1951-57) for the buildings in Chandigarh and Ahmedabad already destined Doshi to take on bigger challenges. Doshi set up his practice in Ahmedabad (1958), a city that had already positioned itself, with work by Le Corbusier and later by Louis Kahn, as a site for demonstrative modern architecture. Doshi also founded an architectural school (1962) that he directed and established as one of the distinguished institutions in India.

Besides his intimacy with the mission of modern architecture, Doshi has remained deeply aligned with the ethos of India’s ancient civilization. Doshi continues to reflect on and draw inspiration from the vast repertoire of Vedic and Hindu traditions. It is this presence of two civilizational and philosophical strands in Doshi’s work that has always offered new possibilities and excursions, as well as debates, in the evolution of modern Indian architecture.

In line with his expanded commitment to architecture involving professional practice, research and teaching, Doshi conceived his practice in a wider term, as a laboratory for the creation of new architectural paradigms. Beginning in the 1970s, Doshi designed and created a miniature complex on a parcel of land at the outskirts of Ahmedabad that came to reflect his synthetic vision of practice and research. Doshi gave that expanded practice the title of Sangath, or “moving together through participation,” that includes his architectural office and the Vastushilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design. Sangath was conceived, as William Curtis notes, as Doshi’s version of an architectural laboratory in the likeness of Corbusier’s atelier at 35, Rue de Sevres, or Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin.

In characterizing Sangath as a turning point that marks both a crystallization of earlier experiments and deliberate movement towards a new stage, three principal themes stand out: an intimate conversation between architecture and landscape, a constructional assembly derived from a climatic imperative, and a choreographed movement in a spatial matrix.

Grounding

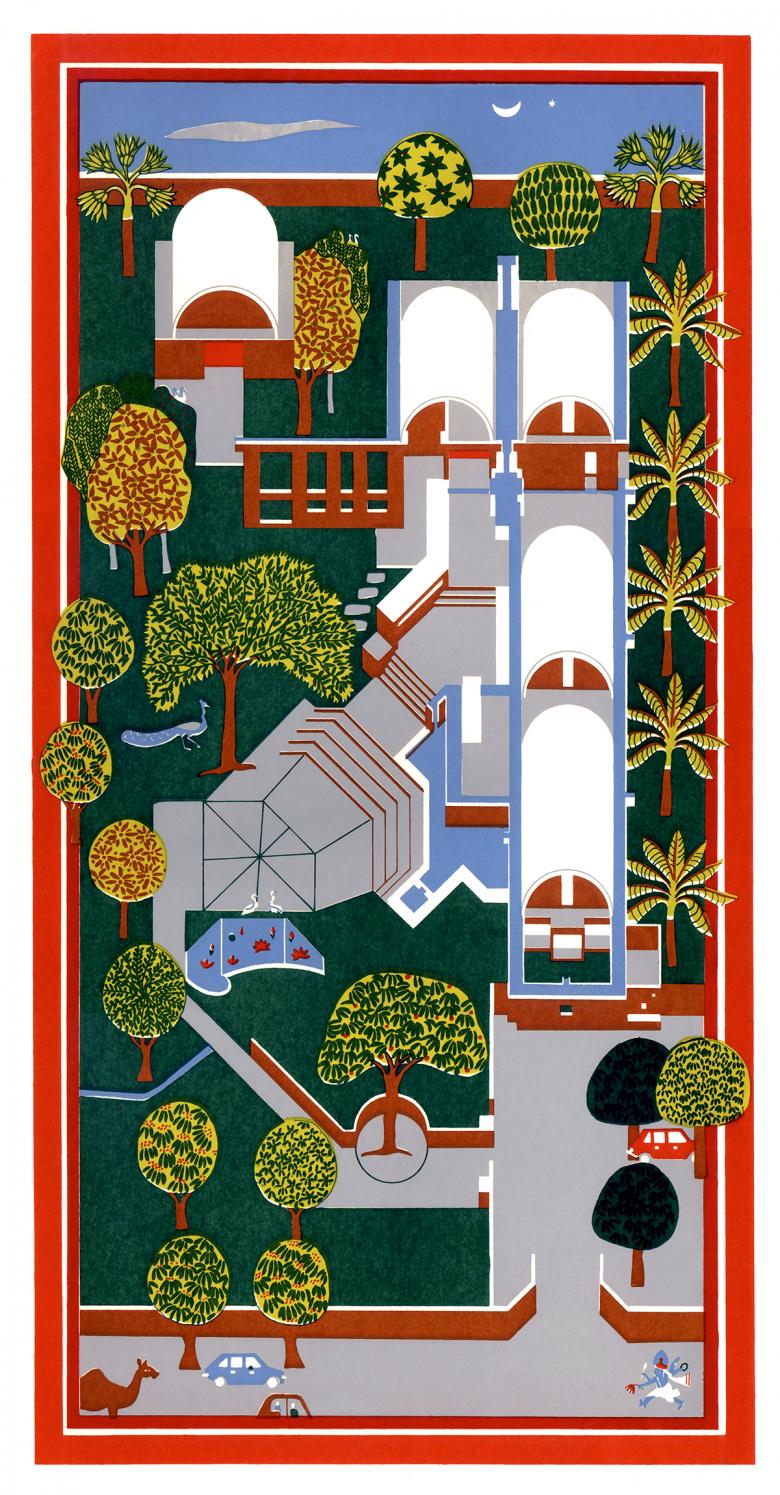

The dominant imagery of Sangath is a group of vaulted shapes oriented in one direction that rises from a constructed landscape of planes, terraces, walls and steps. Water runs along the interstices of the vault, on channels and troughs, often cascading down, to create a pool. While the interiority of the building is a mystery from the exterior, a subterranean possibility is already indicated in the overall ensemble. The “miniature” drawing series generated by Doshi following the construction shows the site with a veritable catalog of architectural and landscape motifs: wall, steps, terraces, trees, artifacts, architectural fragments strewn in the larger landscape.

What immediately characterizes the physiognomy of Sangath is the proposition of architecture as a topographical manipulation. Producing an ambiguity between building and landscape, the configuration is better understood as something evolving from the ground as if sculpted from it.

While the compact ensemble sits on the site as if it has been there for a long time, architectural critics have suggested a few metaphors for it: a group of buildings on a hill, a small village, or a traditional building grown from the ground. A reference to traditional Indian architecture invoking an earth building or domical architecture is only allusive and without any particularity. However, a suggestion for a village is possible which one encounters in a path on a hilly terrain as an ensemble of buildings. An Indian context is more compellingly present in the climatic responses and peripatetic experience on the site. Some of the textural modulation, although suggestive of the work of the Spanish-Catalan architect Josep-Maria Jujol (1879-1949), with whom Doshi has expressed a new kinship, may also be found in certain vernacular traditions of India.

Sangath’s figural alignment may be closer to the other repertoire of Le Corbusier that involves a deeply imbricated mutuality between building and landscape rather than the polemical antitheticality represented in the Swiss-French master’s cubic projects. Two residences designed at the same time by Le Corbusier for Ahmedabad represent this dual and divergent strands: Villa Shodhan as a tropical reincarnation of the cubic Villa Savoye, and the Sarabhai House as recalling an earth-hugging Mediterranean vernacular. Sarabhai House, especially with its Catalan vaults, structural parallelism, grass-covered roof, and clear “merging” with the landscape exonerated the territorially detached ideology through, what Le Corbusier described as, a “pact with nature.” The grounded physiognomy of Sarabhai House can be traced back to Le Corbusier’s consistent attention to translating vernacular types, works that were carefully left in the background in the prime-time of his cubic ideology in the 1920s. The strand of this series of work proceeds from his own Weekend House with the vault and grass roof (1920s) to the radical post-war design of Maison Jaoul (1951).

Sangath, in bringing to the foreground the ancient relational theme of architecture and landscape, and challenging the “twoness” of the two, also remains an homage to the other Le Corbusier. Doshi’s new propensity for a collaboration between architecture and landscape in which the continuum of the land-form dilutes the autonomy of the building-form creates a deliberate and rich ambiguity. Realizing the ontological inevitability of a building sited and emplaced, Doshi presents Sangath as an affirmation of architecture as a “landscape event.”

Doshi’s subterranean quest, and a profound mutation of the cubic paradigm inaugurated at Sangath, turns towards the mythological – the realm of ruins and monsters – finding its explicit expression for the gallery designed for the iconoclast artist M.F. Husain, the Husain-Doshi Gufa at a site not far from Sangath. Starting from Sangath, Doshi increasingly seeks mythological verification in the grounding of architecture, and valorizing a primordial relationship with the earth. While at Sangath, embedding part of the building into the ground was carried out as a tectonic and climatic strategy, the Husain-Doshi Gufa was conceived as some kind of reptilian creature slithering in the ground.

One had to enter that part-reptilian and part-cavelike project through a mouth-like orifice. Doshi himself speaks of dream encounters of divining the site and figuring out the form-shape. The elaboration of a subterranean creature-form is not unlike a resurrection of Vrtra, an aquatic-terrestrial monster in Vedic mythology who was once slayed by the celestial god Indra. This is not unlike Pythia slaughtered by Apollo in Greek imagination to inaugurate a new imperium of the celestial over the terrestrial. Such imagery points to Doshi’s engagement with ancient Vedic and Hindu narratives, and his own deeply personal oneiric imagination in form conception. With the deep and ancient symbolism of the cave, the Gufa provokes a rethinking of the original conditions of architecture submerged in the onslaught of a marketplace dynamic and the displacement of sacrality in the everyday life.

A disposition for an earth-bound configuration is also displayed in other projects whenever an opportunity offered itself. Even for a project with pragmatic currency such as the National Institute of Fashion Technology in New Delhi (1997), and one dressed up a little with postmodern paraphernalia, Doshi was intensely attentive to discovering and digging up an ancient well that produced an excavated parti in the courtyard of the project site.

Doshi’s Sangath phase speaks of his attempt to literally dig down into some primordial depth for a new foundational and ontological verification for architecture in India. “I tried to listen to the vibrations and activities that lay deep in her womb,” Doshi confesses. “The earth always rekindles many dormant ideas in me.” Even though Sangath does not speak of any particular architectural tradition of India, it proposes a new mythos in the tradition. While none of the themes at Sangath match up to a particular tradition or practice, it appears to be in an easy and natural collaboration with the site, as if it has been there for a long time.

(Partial Text)